June 21st, 2024

By Kyo Lee, a Grade 11 WRDSB student.

Grade 11 students across the Waterloo Region District School Board (WRDSB) are earning their compulsory English credit while expanding their knowledge about First Nations, Métis, and Inuit experiences and perspectives . In the 2023-24 school year, the WRDSB has joined 30+ Ontario school boards in offering NBE (English: Understanding Contemporary First Nations, Métis, and Inuit Voices) board-wide. Staff, teachers, and students alike have played important roles in the implementation of this significant change.

Across the School Board

Crissa Hill, Superintendent of Student Achievement and Well-being at the WRDSB, supported the implementation of the NBE course, including leading professional development for instructors.

Crissa says the goal of offering the NBE course was in part to meet the Truth and Reconciliation Commission’s Call to Action #64. The course was “something that was under our control that we could do without having to wait on the actions of larger governments.” She explains that it adds to Waterloo Region and the WRDSB’s reputation as an innovation hub in the aspect of culture: “We are an early adopter…we’re doing the right thing because it’s the right thing to do.”

Crissa explained how NBE benefits students in two ways: “For students who identify as First Nation, Métis or Inuit and their families, it will allow them to feel a sense of belonging in the WRDSB, she says. “For all other students, it will allow them to develop intercultural understanding, empathy and mutual respect.”

Crissa also cites Anishinaabe scholar Niigaan Sinclair in identifying the capacity to work with and understand Indigenous perspectives as a 21st century employability skill: “We want to give our students the best opportunity to thrive in the world that’s coming.”

“I am Mi’kmaq, and in my own learning experience as an Indigenous person in a public school system, there was a lot of misunderstanding,” Crissa says, noting that she would have personally found the NBE course helpful as an Indigenous student. “The power of being exposed to people who look like you and act like you, and have similar experiences helps you have a positive…identity to aspire to be.”

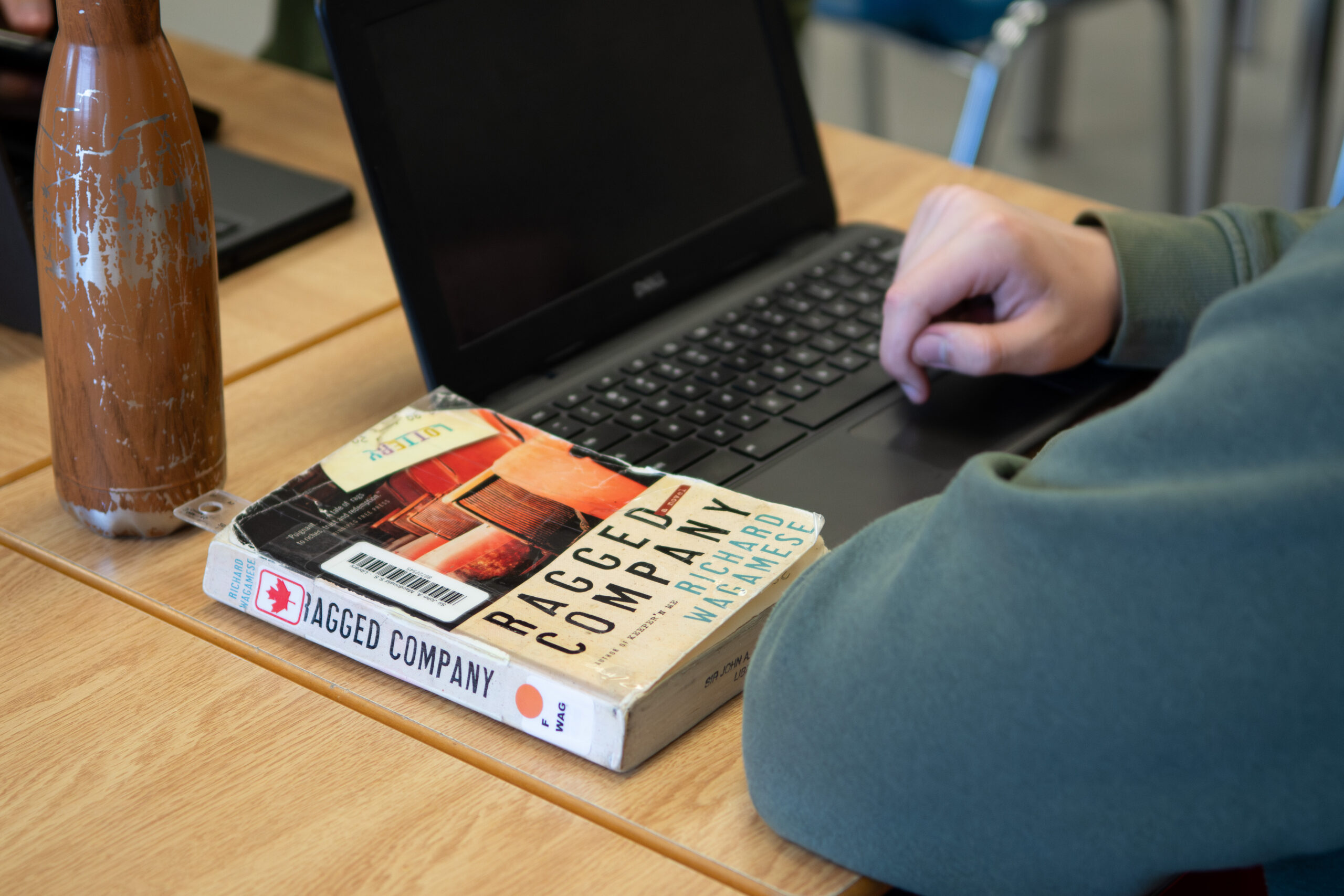

In September 2022, the WRDSB started a year-long learning series to help administrators support teachers in offering the NBE course. Additionally, they were able to provide resources for each school to purchase materials such as books, licences, and documentaries to create a vibrant course fit to their schools, as well as support teachers who wanted to pursue additional qualifications in Indigenous education. WRDSB’s Indigenous Learning Team (ILT) continues to work with English departments. Crissa says, “we want the teaching staff to feel comfortable and confident.”

Crissa also mentions she has “heard feedback from families that having their child in this course is allowing them to have interesting and important conversations at the dinner table.” By impacting students, the NBE course has an amplified effect, by shaping student thinking and catalysing a shift in the wider community.

In the Classroom

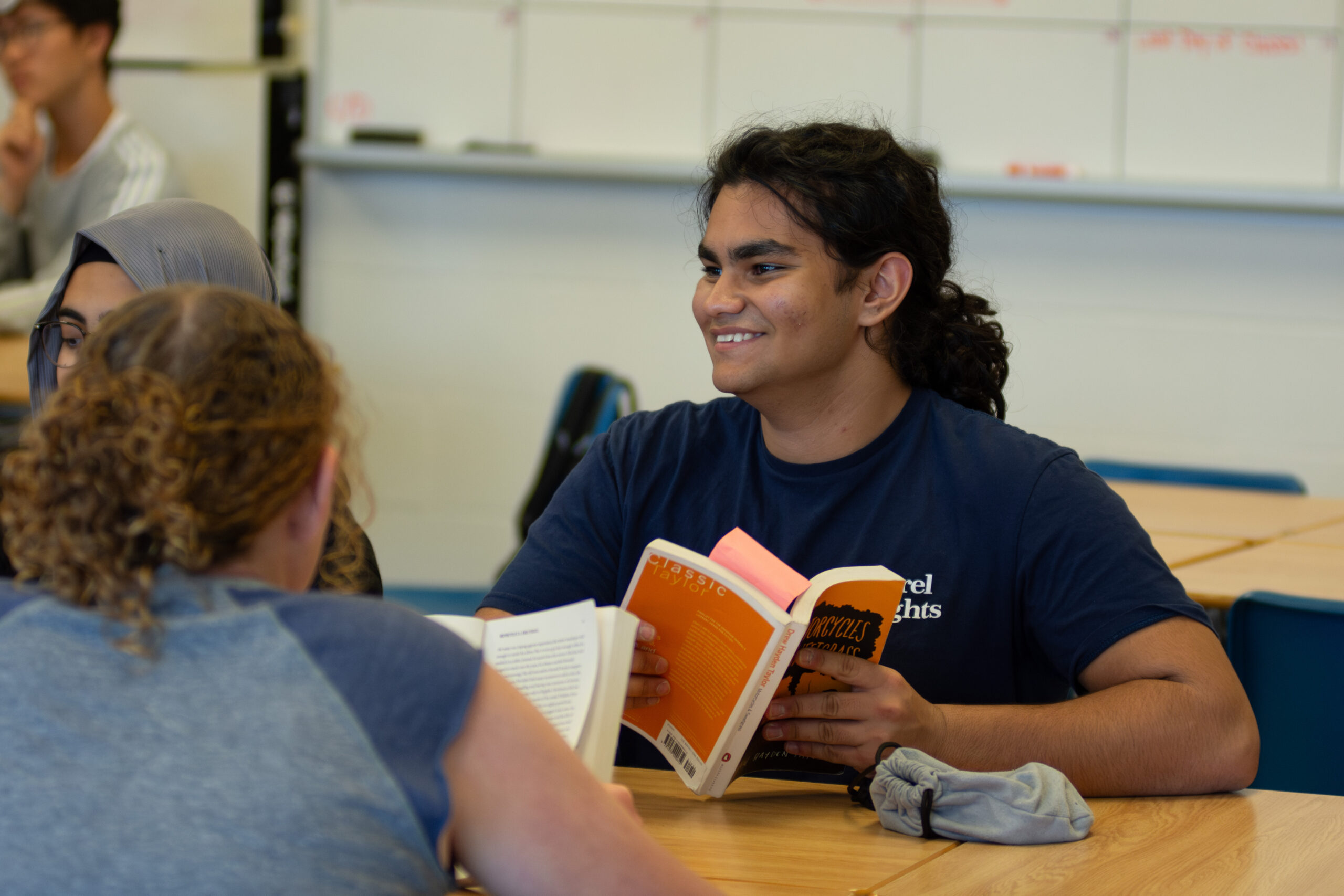

Jackie Araujo, an English teacher at Laurel Heights Secondary School (LHSS), is in her third year of teaching the NBE course.

The need to have more Indigenous voices and perspectives became apparent, especially with LHSS’ name change in 2021. Laurel Heights became one of the first schools to transition all Grade 11 university-level courses to NBE 3UI which required work from “many dedicated people, first from students who showed up to class open and ready to dive into this new curriculum” as well as “English department members, the WRDSB Indigenous Learning team, and the school principals and VPs,” says Jackie. She also notes “it takes a lot of work behind the scenes to launch a new curriculum, and we were excited to learn alongside students.”

Jackie explains the NBE course has the “same competencies as the ENG 3UI curriculum, but with an added focus on responsible citizenship.” She believes that “Truth and Reconciliation is everyone’s responsibility, and the inclusion of historical and current truths is part of a comprehensive education. When we’re silent about the reality of Truth and Reconciliation, we leave room for harm to continue.”

Jackie’s favourite part of teaching the NBE course, same as teaching in any subject, are the students: “Making space to learn about backgrounds, cultures, and experiences in connection with the voices we are uplifting in this course has been such a wonderful experience.” She believes that students “deserve a fulsome education, and this includes listening to, valuing, and understanding contemporary First Nations, Métis, and Inuit Voices.”

The Student Perspective

My name is Kyo Lee, and as a Grade 11 student, I completed the NBE course in the first semester of the 2023-24 school year. I want to share my thoughts about the NBE course, but recognize that this is a reflection of my own experiences and does not represent all students.

English classes are powerful; the materials it uses, the message behind them, and the thoughts it consciously and unconsciously provokes, all stick with students. So as students and educators, it is important to frequently reflect on the media we consume, the texts we read, and the ideas to which we are introduced. As we commit to Truth and Reconciliation, it is necessary that students are given the opportunity to interact with authentic, contemporary First Nations, Métis, and Inuit voices in order to widen our collective viewpoints and disable our biases.

For a long time, our understanding of English class and the types of text it can host has been narrow. But literature does not have to be exclusive, centuries-old, or a part of the Western canon. English class is multitudinous in function, but in its purest form, it simply introduces students to the power of language.

This learning is especially important in the process of Reconciliation, as it demonstrates how language can be a form of activism and truth-finding. Especially for students who may not have seen the power of literature in the context of their identity, the NBE course gives them a new set of tools, including the space and reason to discover the current power of First Nations, Métis, and Inuit creators. It exposes students to new ways of writing, new ways of thinking about literature, and new ways to understand themselves in the literary space. The experiences offered by this course help to teach students how to use the power of language to their advantage.

The course is a part of building a new generation of informed citizens. As Crissa put, “Reconciliation isn’t something that’s going to happen by accident. It is something that has to happen intentionally.” Not just inside the classroom, but beyond it. It is now a part of our responsibility as students who have completed the NBE course to use what we have learned intentionally.

Through this learning experience, I became a more compassionate reader and a more conscious writer. But most importantly, I became a better student, a better inhabitant of Canada, and hopefully a more empathetic person.

#StudentVoice Series

This article is written by a WRDSB student and is part of the Student Agency and Voice program. Student journalists embody WRDSB’s commitment to creating space for students to tell their stories. They are ambassadors for their peers as they share their personal experiences and stories about their schools and communities in their unique voices.

Categories: News